Dive Into Park Chan-wook’s Daring Korean Cinema

Park Chan-wook and his gamut of Korean films have gained visibility in the last two decades, reaching glory from as early as 2000 with water-tight films like Joint Security Area. His style is unique, bending his adopted signature of indulgent violence with ironic humour, horror, illusion-making and gritty sex. All these themes combined make a viscous pulp of fiction; a pancake of surrealism (if you’ve ever tasted one). To question whether you were lucid dreaming after watching a Park film would probably be a compliment to the man re-defining Korean Cinema and niche storytelling. Here I will be discussing some of Park’s notable films of violence and provocation. Let’s dive right in, shall we?

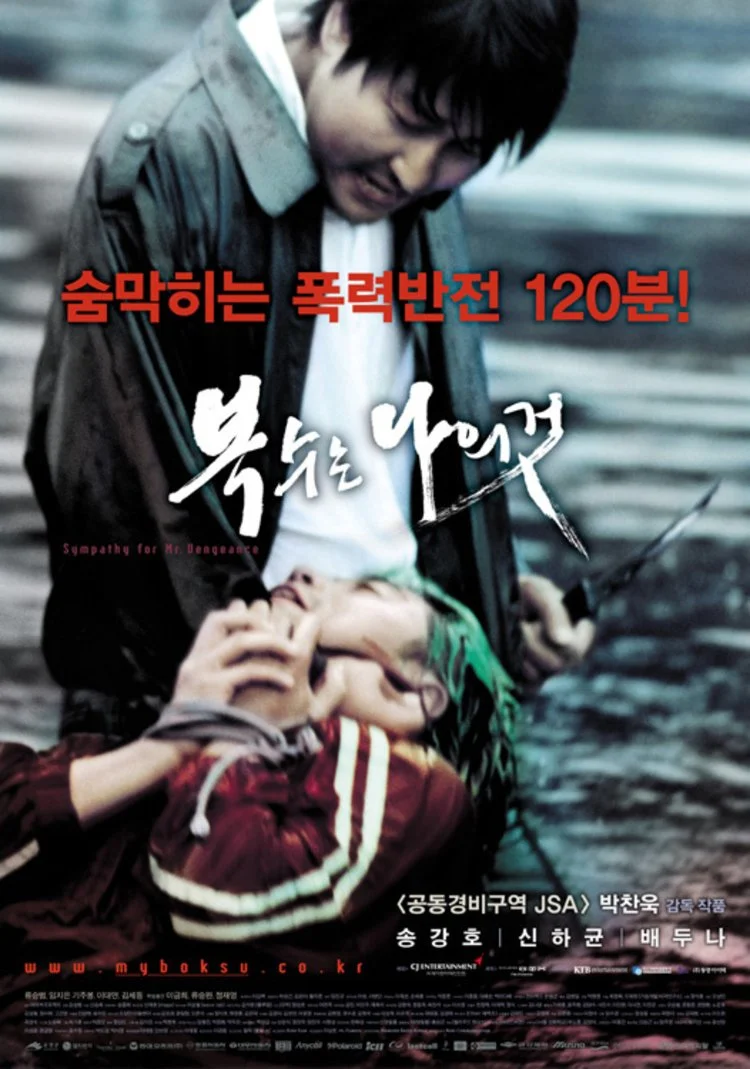

Sympathy for Mr Vengeance (2002)

Sympathy for Mr Vengeance was directed by Park and co-written with Mu Yeoung Lee in 2002. Out of the blocks, the first ten minutes starts off noisy with a continuous cluttered aesthetic, chronicling the cloud of city life and the desperation needed to survive in a beautiful but equally disappointing world. A world designed by Mr Park of course. As the title suggests, ‘revenge’ is the topic of exploration in this two-hour film but is it ever the answer? The character Ryu is deaf, works slavishly in what looks like a steel plant and is burdened with his ailing sister who is in desperate need of a kidney. Sadly, in the first twenty minutes, he is duped out of 10 million Won… and his kidney, spiralling this story into a series of unfortunate events, including the kidnapping of his former boss’s daughter. This final act of desperation will gather enough ransom money to save his sisters life—a shame he can’t save his soul in the process. A depression of themes follows including murder, suicide, despair, and deception, fuelling Park’s conceptualisation of revenge for each character who craves it. This then steam rolls into the second part of the film as we follow the revenge of a father, seeking to rescue his daughter by any violent means possible.

A gorgeous palette of teal-green, reddish-pink, and yellow made me fall in love with this film so, in the quieter moments of dialogue, or where the characters are interacting with a cluttered or spacious landscape, the saturated colours keep us transfixed with each character’s desperate plight. Ryu’s hair is also dyed green, perhaps to symbolise his passivity with his brutalist life events, which seem out of his control. Also, as Ryu is deaf, everything is heightened around him and as the audience we sympathise with his obliviousness. Did you know Sympathy for Mr Vengeance was the first film to have a deaf sex scene? A true mastery of storytelling that some may dare to imagine, if at all; a light-hearted scene which humanised Ryu and real people with disabilities. Here we also get an insight into Park’s sense of humour and beautifully twisted commentary on human nature. As the final moments of the film reaches a crescendo of violence, we are left tying the plot together marvelling at the brilliant breadcrumbs that Park left us all along.

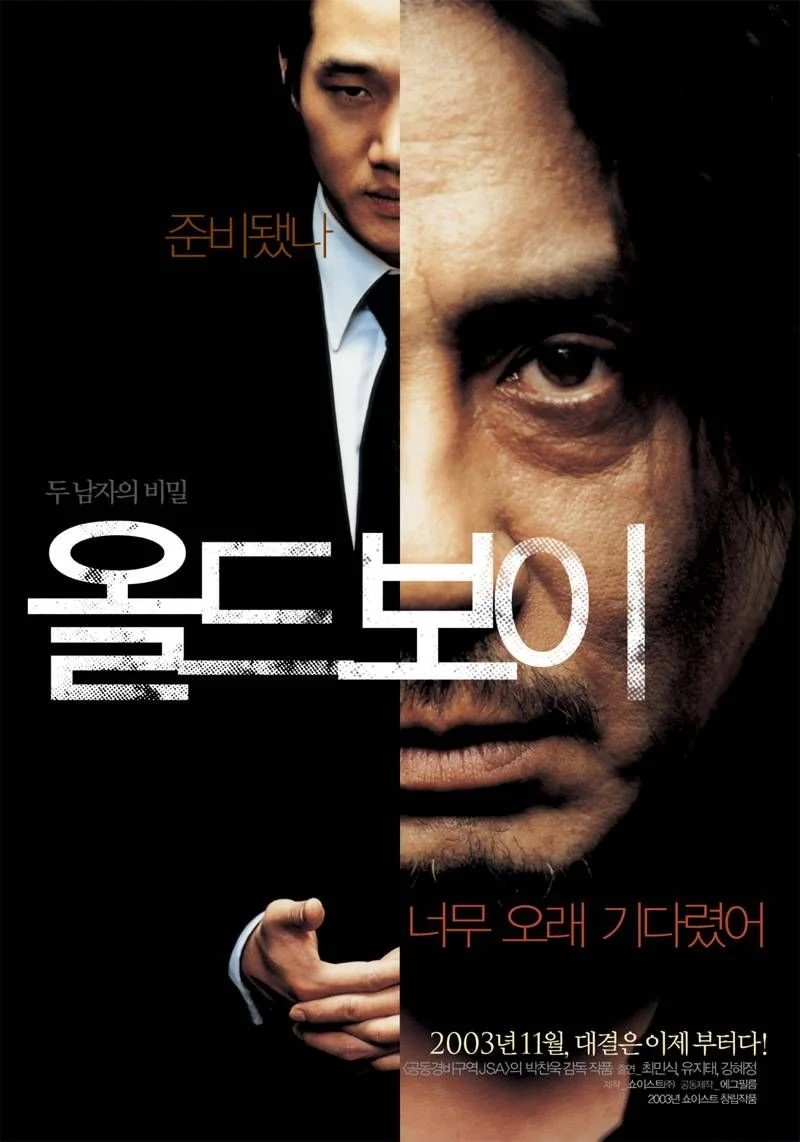

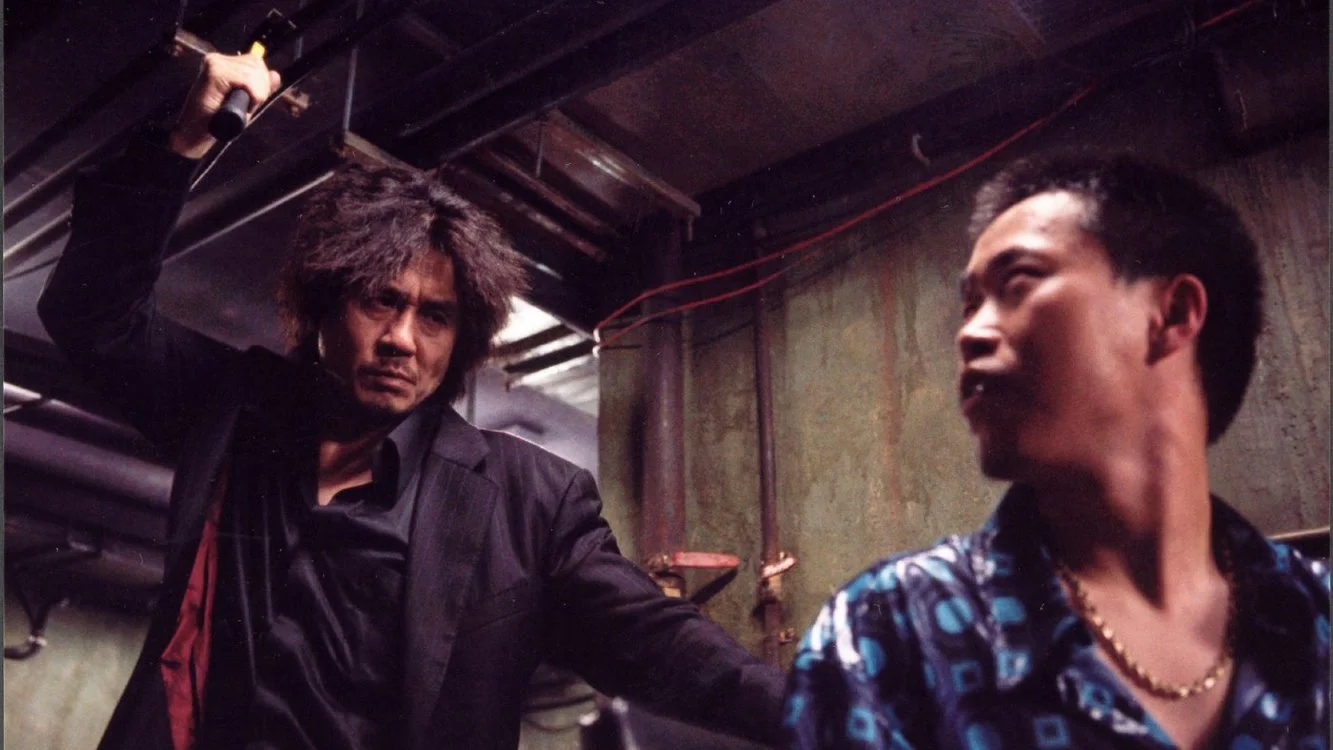

Oldboy (2003)

In part two of Park’s Vengeance trilogy, this 2003 masterpiece came right off the back of Sympathy for Mr Vengeance, which might be considered an audition for Park’s future kooky storytelling and stylised use of colour, violence, and humour—like a trusty pocketknife. No Boy Scout camp in sight, yet honouring his wild imagination, Park spits out a story that is as sexy as it is surrealist with a shiny underworld of violence in his revenge saga. Starring Choi Min Sik as Oh Dae Su, a man randomly kidnapped and imprisoned in a cell with gloomy hotel décor, yet the location is unknown. As the months and years go by, Oh Dae Su begins his prison break so to speak, carving out a crawl space for his escape, only to find that it is positioned very high up on a building. The decision to stay or jump is made for him as he is hastily hypnotised, released, forced out into the ‘real world’, and persuaded to find his captor or face undisclosed consequences. The themes presented in this film go much deeper into Park’s skewed arc of family, love and of course revenge.

Nothing is ever just random in Park’s films because everything ties into his stories either leaving deliberate loose ends or concrete trails. For example, the word ‘Evergreen’ which is an important connection for Oh Dae Su’s character spheres around so many points on his mission as well as highlighting a cryptic message from Park himself: that our thirst for revenge will always exist but cannot be easily quenched. A polarising scene where Oh Dae Su eats a live octopus unfolds this message more clearly as he depravingly feasts on the sea creature. Without drowning in theatrics, the Old Boy soundtrack is a seductive siren to our ears accompanying the well-choreographed fight scenes, inducing a therapeutic visual sequence of playing a video game. These moments feel like Park has gotten into his stride as his stylised use of violence and delayed gratification of violence is used superbly.

Lady Vengeance (2005)

Lady Vengeance is the last puzzle piece In Park’s Vengeance trilogy and does it end on an elegant high. This 2005 feature stars Lee Yeong-ae as ‘kind-hearted’ Geum-ja Lee, who was framed for the kidnapping and murder of four primary school children. The detective in question, II-woo Nam is the catalyst which wrongfully sent Geum-ja Lee behind bars for thirteen years. In an irony of sorts, Geum-ja seeks repentance by helping four women inmates, in the prison she regretfully called home during her sentence. During this journey into Geum-Ja’s early history as a young teen to the woman that she is now seeking redemption and not immediate revenge, ironically, she is still trapped behind her sad existence. After her release, her quest to get favours from the four ex-inmates she helped, propels her to find the real perpetrator of the savage crimes. Here, one theme laid bare is sisterhood which was an empowering taste throughout Geum-ja’s story. Other themes present include motherhood, control, survival, and revenge.

I enjoyed the sisterhood theme which helped facilitate Geum-ja’s anger because although it begins unravelling at its seams, her support network keeps her level-headed, sort of. This attitude is felt when she is finally released from prison wearing nothing but a silk dress with heels, walking out carefree into the freezing winter day. This suggests that her vengeance is sustaining her to the point that she is impenetrable to even the elements, symbolising how nature can’t right these wrongs—she must take matters into her own hands. Moreover, the real takeaway from this film is that the women who come in and out of her story are also victims of circumstances either out of their control or otherwise. This leaves a sour taste towards the end of the movie as we realise, that we are all victims to wanting revenge at some point in life. A particular night scene where Geum-Ja Lee is walking down a spiral of stairs feels important because it lends an eye towards Artist M.C Eschers drawings based on the endless ‘Penrose stairs’. Here, Park continuous his illusionary obsession with stairs, mastering the shadows of the night, subtly foreshadowing that Geum-ja Lee’s path for vengeance is never ending, lonely and painful.

Thirst (2009)

A graduation of all of Park’s previous stylistic nuggets and quirky violence is blended into a film that is just as intense albeit more controlled. Produced in 2009, a good four years after his last revenge themed debut, he tells a story about a priest who is infected with vampire blood during a trial vaccine experiment leading to his thirst for carnal desires as well as human blood. Starring his long-time collaborator, actor Kang Ho Song plays Sang-hyun, a priest who had good intentions of saving people’s lives physically and spiritually but is now harbouring his own demons. Already, the simmering themes of lust, religion, the supernatural and violence, climax into a literal feast for the eyes. Well-done only the way Park knows how to. Sang-hyun’s lustful cravings lead him into the arms of Tae-ju who may or may not be a compulsive liar, deluded by her abusive living situation and marriage. It’s Sang-hyun’s pulsating desire for Tae-ju’s body that leads him to murder her babyish husband. And eventually once he falls for her mind, only then does he start to see Tae-ju’s lies and greed unravel itself. It is this unravelling that continues throughout the film, as ghosts come to haunt the ‘living dead’ and the hunt for blood continues.

Parks films are often focused on each protagonist’s plight into the unknown so his opting for a more coherent story made this film more relaxing amidst the almost cartoonish gore of blood. I really enjoyed this aspect of Thirst, like most of Park’s violent dramas, because they explore the underlying desperation that arise because of trauma. In the case of Sang-hyun, his new status as a vampire means that he cannot surface during the day. Park uses shots with mirrors to show the blemishes that ravages Sang-hyun’s skin until he can get some human blood to recoup during the night and regain his smooth complexion. These moments are especially captivating because they quickly build up the distorted reality that Sang-hyun is living in, posing the harsh illusion of his purpose as a priest and a man. Overall, Park’s use of absurdist humour suggests that in our quest for revenge, we still must eat, sleep, be haunted by our demons and do other necessary mundane things to live another day, essentially.

Was it all an illusion? The burning question that may leave you after watching the last instalment of Park’s revenge trilogy or the confidence of his playful direction with Thirst. Park is a beast of a director in the South Korean Film industry and his storytelling combined with a signature colour palette help maximise his use of indulgent violence and humour, either to create passivity or absolute obsession by his audience.